Today in North African history: the 1969 Libyan coup

A group of Libyan military officers topples the country's monarchy in favor of a republican government led by Muammar Gaddafi.

If you’re interested in history and foreign affairs, Foreign Exchanges is the newsletter for you! Sign up for free today for regular updates on international news and US foreign policy, delivered straight to your email inbox, or subscribe and unlock the full FX experience:

The Arab world experienced quite a number of coups in the 1950s and 1960s. Syria went through three coups in 1949 alone—yes, OK, that isn’t the 1950s, but it’s close enough—and another in 1951. Egypt had a major one in 1952—perhaps you’ve heard about that one. Then Syria had another in 1954, Iraq had one in 1958, Syria had still another in 1961, and Yemen got into the game in 1962. We’re not done yet. Syria (yet again) and Iraq both experienced coups in 1963, Algeria in 1965, and Syria again in 1966. Rounding out the period, Libya experienced a coup on September 1, 1969, which is our subject today. Not only did it jump start Libya’s development into a modern nation-state—a process that admittedly may have reversed itself to some degree by the time you’re reading this—but it introduced the world to one of the most prominent Arab leaders of the second half of the 20th century.

There were several causes behind this trend toward coups, and obviously the precise mix of causes is a little different for every country in question, but the 1952 Egyptian coup that brought Gamal Abdel Nasser to power was a big trend-setter. Nasserism—a hybrid of socialism, republicanism, anti-imperialism, Arab nationalism, and a few other isms I’m sure I’ve missed—began to look pretty good to Arabs living under weak, corrupt regimes that were (except in Yemen’s case) additionally tainted by the fact that they’d been handed power by France and Britain as those two former colonial powers were on their way out of the region. Nasser became the model for several later movements, and even got directly involved in them in a couple of cases (Yemen being the best example).

But Nasser—though he might have disagreed—didn’t emerge out of nothingness to guide the Arab world through the turbulent mid-20th century. If we’re looking for one big antecedent to all of these coups the strongest candidate is the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. The thoroughness of the Israeli victory in that war discredited those post-colonial Arab governments and gave rise to internal opposition. Foreign intervention played its part, as well. Syria’s four pre-Nasser coups were partly motivated by the 1948 war, but the one in March 1949, which kicked everything off, was also backed by a US government eager to grease the wheels for the construction of the Trans-Arabian Pipeline from eastern Saudi Arabia to Lebanon. Syria underwent so many coups in this period that it even had one against Nasser, in 1961, which pulled Syria out of the United Arab Republic, its short-lived (1958-1961) political union with Nasser’s Egypt.

Anyway, the point is that this was a pretty messy time in the Arab world. But for most of it, Libya was relatively quiet. King Idris was Libya’s first (and only) post-colonial king, having united the three regions of Italian Libya (Tripolitania in the northwest, Cyrenaica in the east, and Fezzan in the southwest) under his control. In around 1916-1917 he maneuvered to become the de facto leader of the Senussi, an austere and politically minded Sufi order popular among the Bedouin tribes of North Africa and particularly among the tribes in Cyrenaica (eastern Libya today). In that capacity, Idris had led the resistance to colonial Italian rule in the 1920s, and he later aided the British during World War II. London, in gratitude, backed his bid to become Emir of Cyrenaica in 1949, then to become Emir of Cyrenaica and Tripolitania (northwestern Libya) together, and finally to become king of a united Libya, including the southwestern region of Fezzan. Britain, always willing to do some limited favors for its Arab clients, then granted independence to Libya in December 1951.

Libya kind of puttered along for most of the 1950s, but in 1959 the best and worst thing that could happen to an Arab country happened to it: somebody discovered oil. Libya suddenly wasn’t destitute, which people liked, but as the 1960s wore on they also noticed that a disproportionate share of all their new oil money seemed to be finding its way to Idris’s bank account, which they didn’t like very much at all. Nasserism’s socialist aspects really appealed to a population that increasingly felt like it was getting a very short end of a very long stick.

Many people in each of Libya’s three historical regions also didn’t like that Idris had centralized authority in his own person, making subjects of tribes that were used to independence or at least to substantial autonomy. In addition, as we noted above was the case with many other post-colonial Arab leaders, Idris’s close relationship with the UK, and then the US, helped to discredit him among his subjects, particularly when the UK and Nasser’s Egypt nearly went to war with each other during the 1956 Suez Crisis and again when Idris declined to join other Arab nations in waging the 1967 Six Day War against Israel. Riots became frequent over this period, as Idris’s public support withered away.

Enter, starting in 1964, the Libyan Free Officers Movement—not to be confused with the Iraqi Free Officers Movement, which was behind that country’s 1958 coup, or the original Egyptian Free Officers Movement, the group behind Nasser’s 1952 coup, or the hilariously named “Free Princes Movement” that tried and failed to overthrow or at least drastically reshape the Saudi monarchy in the early 1960s (with Nasser’s backing). These guys, officers mostly out of the Libyan military signals corps, modeled themselves quite explicitly after Nasser’s movement in Egypt. They even had their very own charismatic young officer who dominated what was supposed to be a group of equals—one Muammar Gaddafi, who had idolized Nasser most of his life.

Now, it was widely known that Idris’s health was failing, and he’d actually signed abdication papers that were intended to turn the kingdom over to his nephew, Crown Prince Hasan, on September 2, 1969. So on September 1, with Idris in Turkey vacationing/getting medical treatment, the Free Officers swept into the palace in Benghazi as well as key government, media, and military targets all over the country, and took control in a bloodless coup. Gaddafi declared the monarchy abolished in favor of the Libyan Arab Republic, and most people were so glad to be rid of Idris that they welcomed the new government with open arms.

The Free Officers now became the Revolutionary Command Council and set about running the country, with Gaddafi wisely participating as merely one voice among many and ensuring the country’s transition to true democr-oh, wait, sorry, I got my notes mixed up. Gaddafi made himself commander in chief of the Libyan military and then systematically rid himself of any competition for absolute authority.

If you’re interested in Idris’s fate, I have to say for a guy who was in such poor health that he’d agreed to abdicate before the coup that forced him from power, Idris lived a good, long time. He died in 1983, at the age of 94, in Cairo.

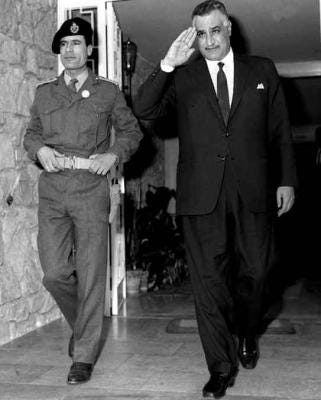

Gaddafi espoused a doctrine that was more or less Nasserist, resting on the twin pillars of Arab socialism and pan-Arabism. He quickly took steps to put that doctrine into practice, arranging a December 1969 meeting in Tripoli with Nasser and new Sudanese Prime Minister Gaafar Nimeiry—the product of Sudan’s own Nasserist military coup earlier that year—where the three leaders signed a charter that was meant to be a preliminary step toward political unification. We’re told that after meeting him, Nasser described his would-be protege, Gaddafi, as “nice” but “naive.” Nasser’s death and the accession of Anwar Sadat caused these plans—and Libyan-Egyptian relations—to go south pretty quickly, and later in life, after most of the Arab world had basically told him to get bent, Gaddafi embraced pan-Africanism as an alternative guiding principle.

I find it challenging to unpack Gaddafi’s legacy because, for one thing, not enough time has passed since his death and, for another, you have to decouple his actual impact from reams of anti-Gaddafi propaganda dutifully spewed forth by Western media. He was an authoritarian who often violently stifled political opposition and showed particular brutality toward non-Arab Libyans. He also undertook reforms that dramatically improved the lives of Libyans who’d been struggling mightily while Idris was counting his oil money. In areas like education, heath care, basic services, anti-poverty measures, and women’s rights, Libya made huge strides under Gaddafi’s rule. Then, starting in the 1990s, he gave back some of that progress in a shift from socialism to free market capitalism, which he undertook at least partly in order to cozy up to the West and get out from under crippling economic sanctions.

Internationally, Gaddafi supported individuals and groups that carried out violent attacks, sometimes against civilians, and made common cause with the far right in Europe. But he also supported the fight against apartheid in South Africa and was justifiably regarded as an anti-colonialist champion across much of Africa, at least until his later turn toward the West—in return for which, of course, NATO helped overthrow him.

In the end part of Gaddafi’s legacy—and it doesn’t reflect all that well on him—has to be the state of the country he left behind. Yes, it was a NATO intervention that did away with him, but that intervention was preceded both by the Arab Spring uprising and Gaddafi’s decision to violently suppress it. What has emerged since Gaddafi’s overthrow is a state of almost total anarchy. Much of the blame for that has to go to the Western powers who intervened to bring more violence to an already violent war, but some of the blame does go back to Gaddafi who, like his contemporary Saddam Hussein in Iraq, ensured that his Libya never developed the kind of political system that could accommodate opposition and forestall rebellion, or the kind of strong institutions that might have been able to stabilize Libya after his death.